Witch Major Holiday Changes The Date Every Year?

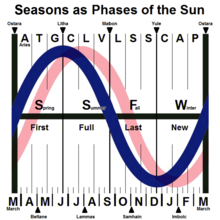

A unlike depiction of the Cycle of the Yr, again from the perspective of the Northern Hemisphere

The Wheel of the Year is an almanac wheel of seasonal festivals, observed by many modernistic Pagans, consisting of the year's chief solar events (solstices and equinoxes) and the midpoints between them. While names for each festival vary amidst diverse infidel traditions, syncretic treatments frequently refer to the four solar events as "quarter days", with the 4 midpoint events as "cantankerous-quarter days".[1] Differing sects of modern Paganism besides vary regarding the precise timing of each commemoration, based on distinctions such every bit lunar stage and geographic hemisphere.

Observing the cycle of the seasons has been important to many people, both ancient and modern. Contemporary Heathen festivals that rely on the Cycle are based to varying degrees on folk traditions, regardless of actual historical pagan practices.[2] Among Wiccans, each festival is as well referred to as a sabbat (), based on Gerald Gardner's view that the term was passed downwards from the Middle Ages, when the terminology for Jewish Shabbat was commingled with that of other heretical celebrations.[3] Contemporary conceptions of the Cycle of the Year calendar were largely influenced by mid-20th century British Paganism.

Origins [edit]

Historical and archaeological evidence suggests ancient heathen and polytheist peoples varied in their cultural observations; Anglo-Saxons celebrated the solstices and equinoxes, while Celts celebrated the seasonal divisions with diverse burn festivals.[4] In the 10th century Cormac Mac Cárthaigh wrote well-nigh "iv groovy fires...lighted up on the four corking festivals of the Druids...in Feb, May, Baronial, and November."[5]

The contemporary Neopagan festival cycle, prior to being known as the Bike of the Year, was influenced past works such as The Golden Bough past James George Frazer (1890) and The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921) by Margaret Murray. Frazer claimed that Beltane (the beginning of summertime) and Samhain (the beginning of winter) were the virtually of import of the 4 Gaelic festivals mentioned by Cormac. Murray used records from early mod witch trials, also as the folklore surrounding European witchcraft, in an attempt to place the festivals historic by a supposedly widespread underground infidel religion that had survived into the early modern period. Murray reports a 1661 trial tape from Forfar, Scotland, where the accused witch (Issobell Smyth) is connected with meetings held "every quarter at Candlemas, Rud−day, Lambemas, and Hallomas."[6] In The White Goddess (1948) Robert Graves claimed that, despite Christianization, the importance of agricultural and social cycles had preserved the "continuity of the aboriginal British festal organisation" consisting of eight holidays: "English social life was based on agriculture, grazing, and hunting" implicit in "the popular celebration of the festivals at present known as Candlemas, Lady Day, May Day, Midsummer Solar day, Lammas, Michaelmas, All-Hallowe'en, and Christmas; it was besides secretly preserved every bit religious doctrine in the covens of the anti-Christian witch-cult."[vii]

The Witches' Cottage, where the Bricket Wood coven celebrated their sabbats (2006).

By the late 1950s the Bricket Forest coven led past Gerald Gardner and the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids led by Ross Nichols had both adopted eight-fold ritual calendars, in order to hold more frequent celebrations. Popular legend holds that Gardner and Nichols developed the agenda during a naturist retreat, where Gardner advocated for celebrating the solstices and equinoxes while Nichols preferred celebrating the four Celtic fire festivals; ultimately they combined the 2 approaches into a single festival cycle. Though this coordination eventually had the benefit of more closely aligning celebrations between the ii early Neopagan groups,[8] Gardner's offset published writings omit whatsoever mention of the solstices and equinoxes, focusing exclusively on the fire festivals. Gardner initially referred to these as "May eve, August eve, November eve (Hallowe'en), and Feb eve." Gardner further identified these modern witch festivals with the Gaelic fire festivals Beltene, Lugnasadh, Samhuin, and Brigid (Imbolc).[3] By the mid-1960s, the phrase Wheel of the Year had been coined to describe the yearly bike of witches' holidays.[9]

Aidan Kelly gave names to the summer solstice (Litha) and equinox holidays (Ostara and Mabon) of Wicca in 1974, which were subsequently promulgated by Timothy Zell through his Green Egg magazine.[10] Popularization of these names happened gradually; in her 1978 book Witchcraft For Tomorrow influential Wiccan author Doreen Valiente did not use Kelly'due south holiday names, instead simply identifying the solstices and equinoxes ("Bottom Sabbats") by their seasons.[11] Valiente identified the four "Greater Sabbats", or fire festivals, by the names Candlemas, May Eve, Lammas, and Hallowe'en, though she also identified their Irish counterparts every bit Imbolc, Beltane, Lughnassadh, and Samhain.[12]

Due to early Wicca's influence on Mod Paganism and the syncretic adoption of Anglo-Saxon and Celtic motifs, the most commonly used English language festival names for the Wheel of the Yr tend to be the Celtic ones introduced past Gardner and the by and large Germanic-derived names introduced past Kelly, even when the celebrations are not based on those cultures. The American Ásatrú movement has adopted, over time, a calendar in which the Heathen major holidays figure aslope many Days of Remembrance which gloat heroes of the Edda and the Sagas, figures of Germanic history, and the Viking Leif Ericson, who explored and settled Vinland (North America). These festivals are non, nonetheless, as evenly distributed throughout the year as in Wicca and other Heathen denominations.

Festivals [edit]

The viii-armed lord's day cantankerous is often used to represent the Neopagan Wheel of the Year.

In many traditions of modern Pagan cosmology, all things are considered to be cyclical, with time as a perpetual cycle of growth and retreat tied to the Sun'southward annual decease and rebirth. This bicycle is too viewed as a micro- and macrocosm of other life cycles in an immeasurable series of cycles composing the Universe. The days that autumn on the landmarks of the yearly cycle traditionally mark the beginnings and middles of the 4 seasons. They are regarded with significance and host to major communal festivals. These 8 festivals are the most common times for community celebrations.[ii] [13] [fourteen]

While the "major" festivals are usually the quarter and cantankerous-quarter days, other festivals are besides historic throughout the year, especially among the not-Wiccan traditions such as those of polytheistic reconstructionism and other ethnic traditions.

In Wiccan and Wicca-influenced traditions, the festivals, existence tied to solar movements, have generally been steeped in solar mythology and symbolism, centered on the life cycles of the sun. Similarly, the Wiccan esbats are traditionally tied to the lunar cycles. Together, they represent the most common celebrations in Wiccan-influenced forms of Neopaganism, especially in contemporary Witchcraft groups.[13] [14]

Wintertime Solstice (Yule) [edit]

Midwinter, known commonly as Yule or inside modern Druid traditions as Alban Arthan,[15] has been recognised as a significant turning signal in the yearly cycle since the belatedly Rock Historic period. The aboriginal megalithic sites of Newgrange and Stonehenge, advisedly aligned with the solstice sunrise and dusk, exemplify this.[16] The reversal of the Sunday's ebbing presence in the sky symbolizes the rebirth of the solar god and presages the return of fertile seasons. From Germanic to Roman tradition, this is the almost important fourth dimension of celebration.[17] [eighteen]

Practices vary, but sacrifice offerings, feasting, and gift giving are common elements of Midwinter festivities. Bringing sprigs and wreaths of evergreenery (such as holly, ivy, mistletoe, yew, and pine) into the dwelling house and tree decorating are also mutual during this time.[17] [19] [xx]

In Roman traditions boosted festivities take identify during the six days leading up to Midwinter.[eighteen]

Imbolc (Candlemas) [edit]

The cross-quarter twenty-four hour period post-obit Midwinter falls on the first of Feb and traditionally marks the get-go stirrings of spring. Information technology aligns with the contemporary observance of Groundhog Day. It is time for purification and jump cleaning in anticipation of the year's new life. In Rome, it was historically a shepherd's holiday,[21] while the Celts associated it with the onset of ewes' lactation, prior to birthing the spring lambs.[22] [23]

For Celtic pagans, the festival is defended to the goddess Brigid, daughter of The Dagda and one of the Tuatha Dé Danann.[23]

Among Reclaiming tradition Witches, this is the traditional time for pledges and rededications for the coming year[24] and for initiation amid Dianic Wiccans.[25]

Jump Equinox (Ostara) [edit]

The almanac bike of insolation for the northern hemisphere (Dominicus energy, shown in blue) with central points for seasons (middle), quarter days (top) and cross-quarter days (lesser) along with months (lower) and Zodiac houses (upper). The cycle of temperature (shown in pink) is delayed past seasonal lag.

Derived from a reconstruction produced past linguist Jacob Grimm of an Old German language form of the Old English goddess name Ēostre, Ostara marks the vernal equinox in some modern Heathen traditions.

Known as Alban Eilir to mod Druid traditions, this holiday is the second of three spring celebrations (the midpoint betwixt Imbolc and Beltane), during which light and darkness are again in residuum, with lite on the rise. It is a fourth dimension of new ancestry and of life emerging further from the grips of winter.[26]

Beltane (May Eve) [edit]

Traditionally the first day of summer in Republic of ireland, in Rome the earliest celebrations appeared in pre-Christian times with the festival of Flora, the Roman goddess of flowers, and the Walpurgisnacht celebrations of the Germanic countries.[27]

Since the Christianisation of Europe, a more than secular version of the festival has continued in Europe and America, usually referred to as May Day. In this form, information technology is well known for maypole dancing and the crowning of the Queen of the May.

Celebrated by many pagan traditions, among modern Druids this festival recognizes the ability of life in its fullness, the greening of the world, youthfulness and flourishing.[28]

Summer Solstice (Litha) [edit]

Midsummer is one of the four solar holidays and is considered the turning point at which summer reaches its height and the sun shines longest. Among the Wiccan sabbats, Midsummer is preceded by Beltane, and followed by Lammas or Lughnasadh.

Some Wiccan traditions telephone call the festival Litha, a proper name occurring in Bede'due south The Reckoning of Time ( De Temporum Ratione , 8th century), which preserves a listing of the (and then-obsolete) Anglo-Saxon names for the twelve months. Ærra Liða (offset or preceding Liða ) roughly corresponds to June in the Gregorian agenda, and Æfterra Liða (following Liða ) to July. Bede writes that "Litha means gentle or navigable, considering in both these months the calm breezes are gentle and they were wont to sail upon the smoothen sea".[29]

Modernistic Druids celebrate this festival every bit Alban Hefin. The sun in its greatest strength is greeted and celebrated on this holiday. While it is the time of greatest forcefulness of the solar electric current, it also marks a turning indicate, for the sun too begins its time of decline as the wheel of the year turns. Arguably the most important festival of the Druid traditions, due to the great focus on the sun and its light as a symbol of divine inspiration. Druid groups ofttimes celebrate this event at Stonehenge.[thirty]

Lughnasadh (Lammas) [edit]

Lammas or Lughnasadh () is the first of the three Wiccan harvest festivals, the other 2 being the autumnal equinox (or Mabon) and Samhain. Wiccans marker the holiday by baking a figure of the god in bread and eating it, to symbolise the sanctity and importance of the harvest. Celebrations vary, as not all Pagans are Wiccans. The Irish proper noun Lughnasadh[4] [31] is used in some traditions to designate this vacation. Wiccan celebrations of this holiday are neither generally based on Celtic culture nor centered on the Celtic deity Lugh. This proper noun seems to take been a tardily adoption among Wiccans. In early on versions of Wiccan literature the festival is referred to as August Eve.[32]

The proper noun Lammas (contraction of loaf mass) implies it is an agrarian-based festival and feast of thanksgiving for grain and staff of life, which symbolises the kickoff fruits of the harvest. Christian festivals may incorporate elements from the Infidel Ritual.[31] [33]

Autumn Equinox (Mabon) [edit]

The holiday of the autumnal equinox, Harvest Domicile, Mabon, the Banquet of the Ingathering, Meán Fómhair , An Clabhsúr , or Alban Elfed (in Neo-Druid traditions), is a modern Infidel ritual of thanksgiving for the fruits of the earth and a recognition of the need to share them to secure the blessings of the Goddess and the Gods during the coming winter months. The proper name Mabon was coined past Aidan Kelly around 1970 as a reference to Mabon ap Modron , a character from Welsh mythology.[34] Amidst the sabbats, it is the 2d of the three Pagan harvest festivals, preceded by Lammas / Lughnasadh and followed by Samhain.

Samhain [edit]

Neopagans honoring the expressionless every bit function of a Samhain ritual

Samhain () is one of the four Greater Sabbats among Wiccans. Samhain is typically considered as a time to celebrate the lives of those who have passed on, and it often involves paying respect to ancestors, family members, elders of the religion, friends, pets, and other loved ones who have died. Aligned with the contemporary observance of Halloween and Day of the Expressionless, in some traditions the spirits of the departed are invited to attend the festivities. Information technology is seen as a festival of darkness, which is balanced at the opposite point of the Bike past the festival of Beltane, which is historic as a festival of light and fertility.[35]

Many Neopagans believe that the veil betwixt this earth and the afterlife is at its thinnest point of the year at Samhain, making information technology easier to communicate with those who accept departed.[14]

Some authorities claim the Christian festival of All Hallows Twenty-four hours (All Saints Day) and the preceding evening are appropriations of Samhain by early Christian missionaries to the British Isles.[36] [37]

Minor festivals [edit]

In addition to the eight major holidays common to most modern Pagans, there are a number of minor holidays during the year to commemorate various events.

Germanic [edit]

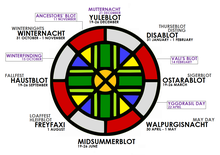

Holidays of the Ásatrú Alliance[38]

- black: main names

- gray: alternative names

- imperial: small common holidays

Some of the holidays listed in the "Runic Era Agenda" of the Ásatrú Alliance:

- Vali's Absorb (14 February)

- Celebration defended to the god Váli and to dearest[38]

- Banquet of the Einherjar (eleven November)

- Celebration to honour kin who died in battle[38]

- Ancestors' Blot (11 Nov)

- Celebration of one's own ancestry or the common ancestors of a Germanic ethnicity[39]

- Yggdrasil Solar day (22 Apr)

- Commemoration of the earth tree Yggdrasil, of the reality world it represents, of trees and nature[38]

- Winterfinding (mid-October)

- Celebration which marks the outset of winter, held on a appointment between Haustblot and Winternights[38] [forty]

- Summerfinding (mid-April)

- Celebration which marks the starting time of summer, held on a appointment betwixt Ostara and Walpurgis Dark[38] [40]

Practise [edit]

Commemoration commonly takes place outdoors in the form of a communal gathering.

Dates of celebration [edit]

The precise dates on which festivals are celebrated are often flexible. Dates may be on the days of the quarter and cross-quarter days proper, the nearest full moon, the nearest new moon, or the nearest weekend for secular convenience. The festivals were originally celebrated by peoples in the middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere. Consequently, the traditional times for seasonal celebrations exercise non agree with the seasons in the Southern Hemisphere or well-nigh the equator. Pagans in the Southern Hemisphere often accelerate these dates past six months to coincide with their own seasons.[xiv] [41] [42] [43]

Offerings [edit]

Offerings of food, drink, diverse objects, etc. take been central in ritual propitiation and veneration for millennia. Modern Pagan practice strongly avoids sacrificing animals in favour of grains, herbs, milk, wines, incense, baked goods, minerals, etc. The exception beingness with ritual feasts including meat, where the inedible parts of the animal are oftentimes burned as offerings while the community eats the rest.[44] [45]

Sacrifices are typically offered to gods and ancestors past burning them. Burying and leaving offerings in the open are also common in certain circumstances. The purpose of offering is to benefit the venerated, show gratitude, and give something back, strengthening the bonds betwixt humans and divine and between members of a community.[44] [46] [47]

Narratives [edit]

Celtic [edit]

It is a misconception in some quarters of the Neopagan community, influenced by the writings of Robert Graves,[48] that historical Celts had an overarching narrative for the entire bike of the year. While the various Celtic calendars include some cyclical patterns, and a belief in the residue of light and dark, these behavior vary between the different Celtic cultures. Modernistic preservationists and revivalists ordinarily observe the four 'fire festivals' of the Gaelic Agenda, and some likewise notice local festivals that are held on dates of significance in the dissimilar Celtic nations.[49] [50]

Slavic [edit]

Kołomir – the Slavic example of Wheel of the Twelvemonth indicating seasons of the yr. 4-point and eight-indicate swastika-shaped wheels were more mutual.

Slavic mythology tells of a persisting conflict involving Perun, god of thunder and lightning, and Veles, the blackness god and horned god of the underworld. Enmity betwixt the two is initiated by Veles' annual ascent up the world tree in the form of a huge serpent and his ultimate theft of Perun's divine cattle from the heavenly domain. Perun retaliates to this challenge of the divine order by pursuing Veles, attacking with his lightning bolts from the sky. Veles taunts Perun and flees, transforming himself into diverse animals and hiding behind trees, houses, even people. (Lightning bolts striking down trees or homes were explained as results of this.) In the stop Perun overcomes and defeats Veles, returning him to his identify in the realm of the dead. Thus the order of the earth is maintained.[51] [52] [53]

The idea that storms and thunder are actually divine battle is pivotal to the changing of the seasons. Dry out periods are identified as cluttered results of Veles' thievery. This duality and disharmonize represents an opposition of the natural principles of world, water, substance, and chaos (Veles) and of heaven, burn, spirit, order (Perun), non a clash of good and evil. The catholic boxing between the 2 besides echoes the ancient Indo-European narrative of a fight between the sky-borne storm god and chthonic dragon.

On the great nighttime (New Year), 2 children of Perun are built-in, Jarilo, god of fertility and vegetation and son of the Moon, and Morana, goddess of nature and death and daughter of the Sun. On the same nighttime, the baby Jarilo is snatched and taken to the underworld, where Veles raises him every bit his ain. At the time of the leap equinox, Jarilo returns across the sea from the world of the dead, bringing with him fertility and jump from the evergreen underworld into the realm of the living. He meets his sis Morana and courts her. With the outset of summer, the two are married bringing fertility and abundance to Earth, ensuring a bountiful harvest. The union of Perun'southward kin and Veles' stepson brings peace betwixt ii not bad gods, staving off storms which could impairment the harvest. Later on the harvest, however, Jarilo is unfaithful to his wife and she vengefully slays him, returning him to the underworld and renewing enmity between Perun and Veles. Without her husband, god of fertility and vegetation, Morana – and all of nature with her – withers and freezes in the ensuing winter. She grows into the one-time and dangerous goddess of darkness and frost, eventually dying by the year's end only to exist reborn once more with her brother in the new yr.[51] [52]

Wicca and Druidry [edit]

In Wicca, the narrative of the Wheel of the Year traditionally centers on the sacred marriage of the God and the Goddess and the god/goddess duality. In this bike, the God is perpetually built-in from the Goddess at Yule, grows in power at the vernal equinox (as does the Goddess, at present in her maiden aspect), courts and impregnates the Goddess at Beltane, reaches his elevation at the summer solstice, wanes in power at Lammas, passes into the underworld at Samhain (taking with him the fertility of the Goddess/Earth, who is now in her crone aspect) until he is in one case again born from Her mother/crone aspect at Yule. The Goddess, in turn, ages and rejuvenates incessantly with the seasons, existence courted past and giving birth to the Horned God.[14] [54] [55]

Many Wiccan, Neo-Druid, and eclectic Neopagans incorporate a narrative of the Holly King and Oak King every bit rulers of the waning year and the waxing year respectively. These ii figures battle endlessly with the turning of the seasons. At the summertime solstice, the Holly Male monarch defeats the Oak King and commences his reign.[56] : 94 After the Autumn equinox the Oak Male monarch slowly begins to regain his power every bit the sun begins to wane. Come the winter solstice the Oak King in turn vanquishes the Holly King.[56] : 137 After the spring equinox the lord's day begins to wax again and the Holly King slowly regains his force until he one time over again defeats the Oak King at the summertime solstice. The two are ultimately seen as essential parts of a whole, low-cal and night aspects of the male God, and would not exist without each other.[14] [57] [58] [59]

The Holly Male monarch is frequently portrayed as a woodsy figure, similar to the modern Santa Claus, dressed in red with sprigs of holly in his hair and the Oak King as a fertility god.[sixty] [61]

See also [edit]

- Ember days, quarterly periods (usually 3 days) of prayer and fasting in the liturgical calendar of Western Christian churches.

- Listing of Neo-Infidel festivals and events

- Medicine cycle, metaphor for a diversity of Native American spiritual concepts

- Solar terms, twelvemonth's divisions in China and East asia

Calendars [edit]

- Celtic agenda

- Gaelic calendar

- Welsh seasonal festivals

- Germanic calendar

- Runic agenda

- Hellenic calendars

- Attic calendar

- Macedonian agenda

- Roman agenda

- Roman festivals

References [edit]

- ^ Williams, Liz (29 July 2013). "Paganism, function 3: the Cycle of the Year". The Guardian . Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ a b Harvey, Graham (1994). "The Roots of Pagan Environmental". Journal of Contemporary Religion. nine (three): 38–41. doi:10.1080/13537909408580720.

- ^ a b Gardner, Gerald (1954). Witchcraft Today. p. 147.

- ^ a b Hutton, Ronald (viii December 1993), The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles, Oxford, Blackwell, pp. 337–341, ISBN0-631-18946-7

- ^ Murray, Margaret. 1931. The God of the Witches.

- ^ Kinloch, George Ritchie. Reliquiae Antiquae Scoticae. Edinburgh, 1848.

- ^ Robert Graves, The White Goddess, New York: Artistic Historic period Press, 1948. Published in London past Faber & Faber.

- ^ Lamond, Frederic (2004), Fifty Years of Wicca, Sutton Mallet, England: Greenish Magic, pp. xvi–17, ISBN0-9547230-ane-v

- ^ Glass, Justine (1965). Witchcraft, the Sixth Sense—and Us. London: Neville Spearman. p. 98.

- ^ Kelly, Aidan. About Naming Ostara, Litha, and Mabon. Including Paganism. Patheos. Accessed 8 May 2019.

- ^ Beckett, John. Enough With the Mabon Hate! Nether the Aboriginal Oaks. Patheos. 11 Sep 2018.

- ^ Valiente, Doreen. 1978. Witchcraft For Tomorrow. London: Robert Unhurt Express.

- ^ a b Zell-Ravenheart, Oberon; Zell-Ravenheart, Forenoon Glory (2006). "Book Three: Wheel of the Year". In Kirsten Dalley and Artemisia (ed.). Creating Circles & Ceremonies: Rituals for All Seasons And Reasons. Book-Mart Printing. p. 192. ISBNane-56414-864-5.

- ^ a b c d due east f Drury, Nevill (2009). "The Modern Magical Revival: Esbats and Sabbats". In Pizza, Murphy; Lewis, James R (eds.). Handbook of Contemporary Paganism. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. pp. 63–67. ISBN9789004163737.

- ^ "Wintertime Solstice - Alban Arthan". Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids. 10 January 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ Johnson, Anthony (2008). Solving Stonehenge: The New Primal to an Ancient Enigma. Thames & Hudson. pp. 252–253. ISBN978-0-500-05155-9.

- ^ a b Zell-Ravenheart, Oberon; Zell-Ravenheart, Morning Glory (2006). "7. Yule (Winter Solstice)". Creating Circles & Ceremonies: Rituals for All Seasons And Reasons. Career Press. pp. 250–252. ISBN1-56414-864-v.

- ^ a b Gagarin, Michael (2010). "S". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome: Volume 1. Oxford Academy Press. p. 231. ISBN978-0-19517-072-6.

- ^ Selbie, John A. (1914). "Gifts (Greek and Roman)". In Hastings, James (ed.). Encyclopædia of Religion and Ethics, Volume 6. New York; Edinburgh: Charles Scribner'due south Sons; T. & T. Clark. p. 212.

- ^ Harvey, Graham (2000). "ane: Celebrating the Seasons". Contemporary Paganism: Listening People, Speaking World. NYU Press. pp. 6–8. ISBN0-8147-3549-five.

- ^ Plutarch. Life of Caesar. Parallel Lives. Vol. Alexander and Caesar.

- ^ Chadwick, Nora G.; Cunliffe, Barry (1970). The Celts. Harmondsworth: Penguin. p. 181. ISBN0-fourteen-021211-six.

- ^ a b Rabinovitch, Shelley T.; Lewis, James R. (2004). The Encyclopedia of Modern Witchcraft and Neo-Paganism. Citadel Press. pp. 232–233. ISBN0-8065-2407-3.

- ^ Starhawk (1979). The Screw Trip the light fantastic toe: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Bang-up Goddess (1989 revised ed.). New York, New York: Harper and Row. pp. 7–186, 246. ISBN0-06-250814-8.

- ^ Budapest, Zsuzsanna E. (1980). The Holy Volume of Women's Mysteries. ISBN0-914728-67-ix.

- ^ "Deeper into Alban Eilir". Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids. eighteen Jan 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ Zell-Ravenheart, Oberon; Zell-Ravenheart, Morn Celebrity (2006). "Book III: Bike of the Year". In Kirsten Dalley and Artemisia (ed.). Creating Circles & Ceremonies: Rituals for All Seasons And Reasons. Volume-Mart Press. pp. 203–206. ISBNone-56414-864-5.

- ^ "Deeper Into Beltane". Lodge of Bards, Ovates and Druids. 18 January 2012. Retrieved xx February 2019.

- ^ Beda, Venerabilis (1999). Bede, the reckoning of time. Liverpool: Liverpool Academy Press. p. 54. ISBN9781846312663.

- ^ "Deeper into Alban Hefin". Club of Bards, Ovates and Druids. 18 January 2012. Retrieved xx February 2019.

- ^ a b Starhawk (1979, 1989) The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess. New York, Harper and Row ISBN 0-06-250814-8 pp.191-2 (revised edition)

- ^ "Gardnerian Volume of Shadows: The Sabbat Rituals: Baronial Eve". world wide web.sacred-texts.com . Retrieved twenty September 2017.

- ^ "Lammas (n.)". etymonline.com. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ Zell-Ravenheart, Oberon Zell-Ravenheart & Morn Glory (2006). Creating circles & ceremonies : rituals for all seasons & reasons. Franklin Lakes, NJ: New Page Books. p. 227. ISBN1564148645.

- ^ Starhawk (1979, 1989) The Screw Dance: A Rebirth of the Aboriginal Organized religion of the Great Goddess. New York, Harper and Row ISBN 0-06-250814-8 pp.193-6 (revised edition)

- ^ Smith, Bonnie Chiliad. (2004). Women's History in Global Perspective. University of Illinois Printing. p. 66. ISBN978-0-252-02931-8 . Retrieved 14 December 2015.

The pre-Christian observance patently influenced the Christian celebration of All Hallows' Eve, just as the Taoist festival affected the newer Buddhist Ullambana festival. Although the Christian version of All Saints' and All Souls' Days came to emphasize prayers for the expressionless, visits to graves, and the role of the living assuring the safety passage to heaven of their departed loved ones, older notions never disappeared.

- ^ Roberts, Brian One thousand. (1987). The Making of the English Village: A Written report in Historical Geography. Longman Scientific & Technical. ISBN978-0-582-30143-6 . Retrieved 14 December 2015.

Fourth dimension out of time', when the barriers between this world and the next were downwardly, the dead returned from the grave, and gods and strangers from the underworld walked abroad was a twice- yearly reality, on dates Christianised as All Hallows' Eve and All Hallows' Day.

- ^ a b c d e f "Runic Era Calender". asatru.org. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ Arith Härger (November 2012). "Ancestors Absorb 11th of November". whispersofyggdrasil.blogspot.com. Retrieved 24 Nov 2012.

- ^ a b William (Bil) R Linzie (July 2003). "Germanic Spirituality" (PDF). p. 27.

- ^ Hume, Lynne (1997). Witchcraft and Paganism in Australia. Melbourne: Melbourne University Printing. ISBN9780522847826.

- ^ Vos, Donna (2002). Dancing Nether an African Moon: Paganism and Wicca in Southward Africa. Cape Town: Zebra Press. pp. 79–86. ISBN9781868726530.

- ^ Bodsworth, Roxanne T (2003). Sunwyse: Celebrating the Sacred Bicycle of the Year in Commonwealth of australia. Victoria, Australia: Hihorse Publishing. ISBN9780909223038.

- ^ a b Thomas, Kirk. "The Nature of Sacrifice". Cosmology. Ár nDraíocht Féin: A Druid Fellowship. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ^ Bradbury, Scott (1995). "Julian's Heathen Revival and the Refuse of Blood Sacrifice". Phoenix. 49 (4 (Winter)): 331–356. doi:10.2307/1088885. JSTOR 1088885.

- ^ Krasskova, Galina; Wodening, Swain (forrad) (2005). Exploring the northern tradition: A guide to the gods, lore, rites, and celebrations from the Norse, German, and Anglo-Saxon traditions. Franklin Lakes, NJ: New Page Books. ISBN9781435658943.

- ^ Meuli 1946

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (1993). The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. Oxford: Blackwell publishing. p. 145. ISBN0-631-18946-seven.

- ^ Bonewits, Isaac (2006). Bonewits's Essential Guide to Druidism. New York, New York: Kensington Publishing Group. pp. 179, 183–4, 128–140. ISBN0-8065-2710-two.

- ^ McColman, Carl (2003). Consummate Idiot'due south Guide to Celtic Wisdom. Alpha Press. pp. 12, 51. ISBN0-02-864417-4.

- ^ a b Leeming, David (2005). "A-Z Entries". The Oxford Companion to Globe Mythology. New York, New York: Oxford Academy Press. p. 360. ISBN0-xix-515669-2.

- ^ a b Hlobil, Karel (2009). "Affiliate 11:Slavic Mythology". Before You. Insomniac Press. ISBN978-one-92-658247-4.

- ^ Lyle, Emily (2008). "Fourth dimension and the Indo-European Gods in the Slavic Context" (PDF). Studia Mythologica Slavica. 11: 115–126. doi:x.3986/sms.v11i0.1691.

- ^ Vivianne Crowley (1989). Wicca: The One-time Religion in the New Age. London: Aquarian Printing. pp. 162–200. ISBN9780850307375.

- ^ Starhawk (1999). The Spiral Trip the light fantastic toe: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Nifty Goddess: 20th Ceremony Edition . San Francisco: HarperOne. pp. 197–213. ISBN9780062516329.

- ^ a b Farrar, Janet & Stewart Farrar; with line illustrations by Stewart; Farrar, photographs past Ian David & Stewart (1984). A witches bible. New York: Magickal Childe. ISBN093970806X.

- ^ Farrar, Janet and Stewart (1988). Eight Sabbats for Witches, revised edition. Phoenix Publishing. ISBN0-919345-26-3.

- ^ Joanne Pearson (2002). A Popular Dictionary of Paganism. London: Taylor & Francis Ltd. p. lxxx. ISBN9780700715916.

- ^ Carl McColman (2002). The Consummate Idiot's Guide to Paganism. Indianapolis, IN: Alpha. p. 121. ISBN9780028642666.

- ^ Raven Grimassi (2000). Encyclopedia of Wicca & Witchcraft. St Paul, Minnesota: Llewellyn Worldwide. p. 219. ISBN9781567182576.

- ^ Wigington, Patti. "The Legend of the Holly King and the Oak King". paganwiccan.virtually.com. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

External links [edit]

- Astronomical cusps and pagan holidays

- Celebrating the Seasons at Circle Sanctuary

- Sun Moon calendar

- Festival Calendar for the Indo-Europeans

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wheel_of_the_Year

Posted by: spragueyoudiven.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Witch Major Holiday Changes The Date Every Year?"

Post a Comment